5 October, 2020

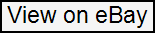

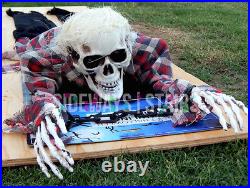

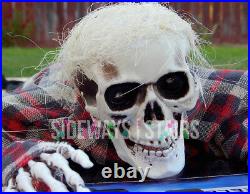

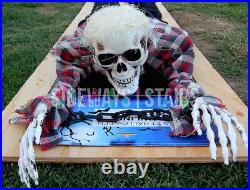

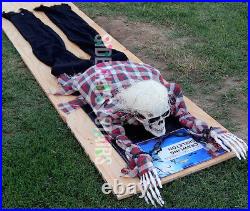

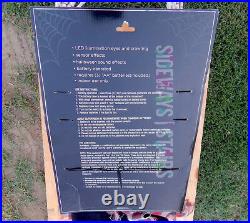

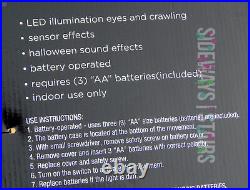

CRAWLING ZOMBIE SKELETON animated prop Halloween decoration plaid shirt creepy